Think of the literature review as an opportunity to show that you’ve actually done your homework and not just read the headlines! It’s basically like piecing together a giant puzzle from all the research that’s been done before you. You dive into books and articles, sort through what’s been discovered, notice where things don’t quite add up, and see what the experts agree on (or not). If there’s a gap or something that everyone keeps missing, it’s time to shine.

But here’s the real point: A good literature review isn’t just a glorified book report. You don’t just list who said what; you connect the dots. The goal? To show how your project fits – are you adding something new, fixing an old misunderstanding, or just picking up where someone left off? Mastering this skill will not only make your work meaningful, but also prove that you really know your stuff. Trust me, nothing impresses a search committee more than someone who can connect complex ideas and make it look effortless.

Overview of a literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize what’s already out there—it actually puts you at the heart of the academic conversation. When a researcher provides a comprehensive review, it’s like joining an ongoing discussion: they show that they know their stuff and can spot gaps or questions that others might have missed. Also, diving into previous research helps avoid old tracks (no one wants to spend months on something that was completed years ago!). Most importantly, however, a thoughtful literature review provides the basis for new research—ensuring that new research does not proceed by itself, but actually builds on and adds to what is already known.

Why is a literature review conducted?

Have you ever tried to dive into a new research topic and felt lost? This is where a literature review steps in to save the day. Basically, it’s your chance to find out what’s already been said about your topic, to pick up on the traces left by researchers who came before you. Here’s why it’s so important:

First of all, a serious literature review puts your research problem into context. You can see what came before, what people have already figured out, and where the conversation is going. In fact, trying to do research without this background is like wandering into a movie halfway through—you might get the gist, but you’ll definitely miss the big picture.

But it’s not just basic information. Literature reviews are great for spotting gaps or weaknesses in what already exists. Maybe there are contradictions in previous studies, or maybe no one has bothered to look at your topic from a certain angle yet. There’s nothing quite as satisfying as realizing you’ve discovered a tiny corner of knowledge that no one else has explored!

Next: the frames. Theoretical and conceptual frameworks sound fancy, but they are basically just lenses that people use to make sense of things. By looking at how other researchers have approached your topic—perhaps they’ve used psychological theory or some complex framework—you begin to see which approaches might work for you.

Methodology is another big thing. Looking at how studios have been designed in the past (what worked, what didn’t) can help you avoid rookie mistakes and choose methods that actually meet your goals.

Also, let’s be honest: showing you’ve read widely will make you look credible. It proves that you’re not just throwing ideas into the void – you’re based on real science, respecting what’s already known, pushing things forward.

And finally? As you do all that research (and sometimes untangle conflicting results), you’ll start to see where your own research questions or hypotheses should be. It’s almost like collecting clues in a detective story until you’re ready to make your big reveal.

Yes, literature reviews may seem dry at first glance, but in truth, they are like the unsung heroes that shape good research from the ground up.

An example of a literature review

These days, when you talk about environmental issues, climate change and biodiversity seem to go hand in hand. Over the past decade, scientists have been trying to figure out exactly what our changing climate means for life on Earth—and, be warned, it’s complicated.

First, let’s look at phenology, essentially a calendar of life events (such as when birds migrate or flowers bloom). A number of studies show that warmer temperatures are changing these natural schedules. For example, Parmesan and Yohe (2003) found that animals in both the northern and southern hemispheres change their migration dates and breeding seasons. But here’s the kicker: not all species adapt synchronously. Thus, strange inconsistencies occur, for example, pollinators appear after the flowers have already bloomed. The consensus seems to be that these timing issues can shake up entire food webs.

Shifting gears to the ocean, things are also messy there. Corals are bleaching, fish populations are moving away from the equator, and even plankton communities are changing as waters warm (Poloczanska et al., 2013). Some sea creatures adapt to pack up and go to the pole; others just don’t do well. It’s like an underwater game of musical chairs, only the stakes are much higher. Researchers agree that this is not just a surface-level problem – it seriously disrupts food supply chains and ecosystem stability.

Rising temperatures on land increase habitat loss in a way that exacerbates other threats already facing wildlife (think deforestation or urban sprawl). Numerous papers have sounded the alarm about the increasing risk of extinction for species that cannot migrate or adapt quickly enough to new conditions (Thomas et al., 2004). Amphibians and montane species seem particularly vulnerable – frankly, grim reading if you care about frogs.

While there is a wealth of research outlining what is already happening, several researchers point out that we still have huge blind spots. How will less studied organisms react? Can ecosystems recover if climate trends change? And what happens when multiple stressors accumulate at the same time? Most people agree that we need more long-term studies in different regions so that we don’t miss the forest for the trees (sometimes literally).

How to write a literature review that is effective

When you dive into writing a literature review, you can’t just throw together a bunch of articles and call it a day. It has some art and definitely some structure to it. Here’s how you’ll typically put it together:

**Intro**: This is your big opening scene. Prepare background information about your topic. Why should anyone care? What’s the big picture here? Explain why this topic is important not only to you, but also in general. Perhaps start with an eye-catching statistic or a question that highlights the importance of the topic.

Once you’ve grabbed attention, state the **goal and scope**: What exactly do you hope to accomplish with this review? Mention your main research question, or if it’s broader, at least outline your main focus – this helps your reader know what to expect (and helps you follow up).

Below is a small outline (think **organizational system**). Briefly describe how you arranged everything. Will you go by theme? Timeline? Method? Figure it out so people don’t get lost midway.

Remember the **importance of research**: Why is this review necessary? How does it fill a gap or offer new perspectives in the field?

Before you finish your introduction, provide a clear **thesis statement**—one clear sentence that represents your main idea or position.

**Body**: This is where the real action happens. Roll up your sleeves and read all those studies you’ve read. Don’t just summarize everything like a laundry list; instead, group them by common themes, viewpoints, controversies—whatever makes sense for your topic.

For each group or department:

– Dig deeper into what these studies have found.

– Point out strengths (perhaps one used innovative methods) and weaknesses (another had a very small sample size).

– Discuss how convincing their evidence is.

– Remember: don’t be afraid to point out disagreements or arguments between researchers – it actually shows that you’re paying attention.

After breaking down the individual parts, take a step back and perform a **synthesis of the findings**. Are there patterns emerging? Are recurring findings or objections worth mentioning?

Identifying **research gaps** is key – what’s missing? Are there any questions that no one has answered yet? Recognize these areas; they may even become inspiration for your future work!

To keep things flowing smoothly, use clear **transitions** from one topic or section to another – this helps readers follow your thoughts without getting bogged down.

**Conclusion:** Time to finish.

– **Summarize the main findings:** Summarize what stood out from all that reading.

– **Highlight Contribution:** State how your review contributes to understanding.

– **Real Applications:** Does what you discovered have practical implications? Could it change practice or guide future policy?

– **Suggestions for future research:** indicate what still needs to be researched. Have a question someone should answer below? Share them.

– **Final Thoughts:** close with a reminder of why all of this is important, not just to you, but to anyone interested in this topic.

And there you have it! A literature review isn’t just an academic box to tick – it can actually be quite engaging (if you let it). Just remember to stay organized, be critical, and don’t shy away from making your voice heard.

Completing a review of literature

Okay, so you’re going to do a literature review. It might seem a little daunting at first, but to be honest, once you break it down, it’s pretty manageable. Here’s how I usually do it:

First, you need to determine exactly what you want to research. Don’t just dive into random articles – start with a clear question or topic. Once that’s resolved, hit the databases! Google Scholar, JSTOR, or any of your favorite digital hangouts. Dig deep and cast a wide net; sometimes you find gems hidden in places you wouldn’t expect.

As you read articles and books, look for recurring themes or big debates in your area. Take notes (seriously, don’t rely on memory here) and jot down anything that jumps out, whether it’s quotes, key takeaways, or even things that make you say “huh!”

The next step? Organize your discoveries so they aren’t just a jumble of random ideas. Maybe that means sorting them by topic, methodology, or year – whatever makes sense for your project.

Now comes the part where you actually write the review. It’s not just a giant summary. You want to connect your sources: compare their arguments, point out agreements or contradictions, highlight any gaps they leave, and tie it all back to your main question.

And finally – never miss this one – check all quotes before submitting anything! (Trust me, nothing ruins a good review like citation errors.)

Of course, it takes some work up front, but it lays a solid foundation for any further research. Who knows, after it’s over, you might enjoy the hunt for new knowledge!

Select a subject and formulate the research question:

aim to investigate how social media platforms – Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat – affect adolescent mental health. Specifically, I want to find out whether regular use increases anxiety or depression and, if so, which parts of the experience (such as comparing yourself to others, cyberbullying, or just being judged late at night) play the biggest role.

Determine the Review’s Scope:

First, determine when you actually need to do a literature review. Is it something that needs to be wrapped up in a couple of weeks, or do you have a little more breathing room? Having a clear deadline will really help keep things in order (and even save you from a last-minute panic session).

Then ask yourself: are you interested in tracking how things have changed over time, or are you focused on what’s happening in the field right now? Sometimes it is very important to get the overall historical picture; in other cases, it makes more sense to simply ignore the latest research.

Don’t forget about geography! Do you want your review to include studies from around the world or stick to a specific region? For example, maybe you’re only interested in North American research, or maybe you’re interested in learning about what’s happening around the world.

And then there’s the nitty-gritty of what counts as “in” or “out.” Figure out what types of sources you will allow. Do you spread the net and include articles, books, conference proceedings – perhaps even gray literature such as reports? Or do you want to stick to peer-reviewed journals only? Be open about which studies are not relevant to your question – you may miss studies that are more than ten years old or studies that do not provide primary data.

Setting up all these guardrails now will make your search and analysis much easier later!

Choose which databases to search:

If you’re diving into research, start with well-known databases in your field. For anything related to medicine or life sciences, PubMed is pretty much the holy grail. People in engineering or computer science tend to use IEEE Xplore, while Scopus and Web of Science are great for a variety of scientific articles from all over the place. And let’s be honest: when in doubt, everyone turns to Google Scholar.

But don’t just stop! If you’re digging into a niche topic, see if there are specialist databases for your area – sometimes those hidden gems have exactly what you need. Oh, and remember your university library catalog or institutional repositories; sometimes they have research papers or theses that you won’t find anywhere else. Check them all out and keep an open mind – you never know where you’ll stumble upon that perfect article you’ve been looking for.

Make Searches and Maintain Records:

Embarking on a research journey is like navigating a vast, complex library where every aisle leads to new discoveries, questions and perspectives. A thoughtful strategy lights the way. Here’s how to structure and document a search method that promotes transparency and reproducibility—a must for any scientific endeavor.

—

**1. Define your research question and keywords**

Begin by distilling your topic into a clear, focused research question. Find out its main concepts. For each concept, consider alternative terms, synonyms, and broader/narrower related words.

*Example:*

Research question: _How does regular exercise affect the mental health of adolescents?_

– Key concepts: “exercise”, “mental health”, “adolescents”

– Synonyms/related terms:

– Exercise: “physical activity”, “sport”, “training”

– Mental health: “psychological well-being”, “depression”, “anxiety”

– Teens: “teens”, “youth”, “youth”

**2. Create Boolean search strings**

Harness the power of Boolean operators:

– **AND:** narrows results (includes all terms)

– **OR:** expands results (includes any given term)

– **NO:** Excludes conditions

*Boolean string example:*

(exercise OR “physical activity” OR fitness) AND (“mental health” OR “psychological well-being” OR depression OR anxiety) AND (adolescents OR teenagers OR youth OR “young people”)

“`

If you wish to exclude a study or population type, enter **NO**:

… AND NOT (Elderly OR Adults)

**3. Using advanced search methods**

– **Abbreviation:** e.g. teenager* will search for teenagers, teenagers

– **Phrase Search:** Use quotation marks for exact phrases like “mental health”.

– **Field Searches:** apply keywords to title, abstract or subject fields where possible

**4. Search Documentation**

Transparency is not a luxury; it is a necessity. Record each iteration of the search carefully:

– **Databases searched:** (e.g. PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science)

– **Search Date**

– **Search string used**

– **Applied filters:** (e.g. language, date sequence, study type)

– **Number of results returned**

| PubMed | 06/01/2024 | (see above) | English, 2014-2024 | 215 |

—

**5. Screening and abstract review**

Carefully review article titles, abstracts, and publication information. Ask:

– Does it directly address the research question?

– Is the methodology robust?

– Is the publication peer-reviewed and reputable?

Enter your inclusion/exclusion criteria.

**6. Link Management**

Let technology be a reliable companion, not a distraction. To:

– Import references directly from databases using browser plugins or RIS/BibTeX files

– Organize articles into folders by topic or relevance

– Annotate and highlight PDF

– Generate citations and bibliographies in your preferred style

*Tip:* always back up your link library and sync periodically across devices.

**7. Review, Reflect, Refine**

The first search is rarely the last. Consider gaps or redundancies. Change keywords, Boolean operators and filters. Document each adjustment.

Examine the Literature:

To sort things out based on the information you provided, here’s how I would view and sort academic sources:

**1. Source quality and compliance**

When reviewing each study or article, I would consider factors such as:

– Who published it (respected journal, peer-reviewed, recent)?

– How closely is it related to the topic or issue at hand?

– It does not matter whether the authors have experience or solid knowledge in this field.

Regarding the study design:

– Did they use randomized control groups or just simple surveys?

– How large was their sample (large enough to make strong claims or too small to be significant)?

– Did they use clear, fair ways to measure their results?

**2. Grouping by main ideas/themes**

As you read through, themes begin to emerge. For example, telecommuting research can be divided into: productivity, well-being, management and technology use. I would sort each source where it fits best.

**3. Gaps, patterns and trends**

Sorting and summarizing makes it easier to see where current research is clustering. For example:

– Lots of data on short-term effects, but little on long-term risks.

– Trends in certain methods (e.g. more qualitative interviews in the last five years).

– Missing voices, such as a lack of samples from minority groups or smaller firms.

This helps you spot which areas are over-explored and where more digging is needed.

**4. Key points and conclusions (for each study)**

I will make notes for each source:

– Main conclusion (did remote work increase productivity or not?)

– Surprising discoveries

– Any solid and well-verified claims

– Any soft spots or creases

**5. Differences and similarities (in studies)**

Sometimes two studies seem to reach opposite results.

– It can be said that working remotely increases happiness, for others – isolation.

– Often the method or example is different: maybe one hired freelancers, the other hired company employees.

I’ll lay out where the studies agree (for example, most say technology is a big factor) and where they don’t.

**6. Synthesis and critical analysis**

In conclusion, a well-lit review weighs all the evidence.

– Are there clear answers?

– Which studies used numbers that relied on stories correctly?

– Some used better management tools, others had too few people.

– Notice where tradition or bias might creep in (was each study from the same region or a narrow group?).

– Where the research is clear, it is worth paying attention – where it is mixed, it is marked for further work.

**Strengths and weaknesses in the research so far:**

*Advantages* may include increased awareness in various fields, better tools and techniques than before, or large sample sizes.

*Disadvantages* can be overreliance on certain data, insufficient diversity of subjects, or short-term thinking.

In short: Sort studies by topic, see how they performed and if their numbers add up, watch for duplicate results or disagreements, and don’t miss areas that need more work. Always note the strongest and weakest elements of the research you find to help guide what comes next.

How to Write and Arrange a Literature Review

If you are preparing for a literature review, organization is your best friend. First, think about how you want to set things up: will you categorize sources based on the methods they used, the timeline of their research, or common themes? Choosing one of these methods from the start will make the rest much easier.

Let’s say you’re choosing topics – perhaps ‘technology in learning’, ‘student engagement’ and ‘assessment strategies’. As you read each article or book, you sort your findings into these buckets. Over time, it’s like putting a puzzle together: patterns (and some contradictions!) begin to emerge. Perhaps one group of researchers consistently finds that classroom technology promotes participation, while another argues that it makes no real difference. These connections are the foundation of your story.

In terms of narrative, a good literature review does more than list studies; it intertwines them. For example, instead of dryly announcing the results, try:

“In recent years, technology has become a driving force for educational innovation (Smith, 2021). Although Smith highlighted increased student motivation, Johnson and Lee (2022) found little impact on overall achievement scores. Clearly, the debate is far from settled.”

When it comes to citation style, don’t forget it! If your professor wants APA, follow it consistently from start to finish. Nothing ruins a flow like switching between citation styles or forgetting to add authors’ names and year.

And don’t forget the strong ending. After tracking all the research and trends, summarize the biggest findings in a few sentences. What did people mostly agree on? Where was everything left unclear? For example: “Research overwhelmingly supports the role of technology in promoting engagement. But evidence that it leads to better learning outcomes is mixed.”

Before signing off, highlight any gaps you see (“Few studies have examined long-term effects” is a classic observation) and make some suggestions for what future research should include (“Future researchers would benefit from following students for several years”).

One last thing, treat your literature review as a living document. It is likely that you will need to update the review as new research becomes available or project directions change. Don’t sweat it; review and review is part of the game.

In short? By being methodical and well-connected, your literature review can be both clear and insightful, giving readers a solid sense of what is known and what questions still remain in the field.

Common questions about literature reviews

What does a research literature review entail?

A solid literature review is the foundation of almost any research project. Think of it as the research world’s version of doing your homework before class – you have to know what everyone has already said. A proper literature review goes beyond summarizing what is out there; it digs deeper, separates research and helps spot gaps or trends in the field. Not only does this save researchers from reinventing the wheel, it also gives them a solid foundation for their own ideas.

Also, there’s more to it than just reading mountain articles. A good literature review helps to form a basic research framework, both theoretical and conceptual. It ties your research into the big picture, showing how your findings fit (or contradict) what has gone before. Honestly, you would be working in a vacuum without this step. So if you want your research to actually be relevant and have context, skipping the literature review is not an option.

Why is writing a literature review important?

Let’s be real: a literature review is basically the foundation of any research paper. Without it, your cabinet would stand on wobbly legs and look pretty lost. It’s more than just a summary—you’re navigating what’s already out there, picking up different approaches, spotting new trends, and observing experimental turns in your field. When you put it all in writing, you not only get your reader hooked; you’re also making sure your fellow experts know you’ve actually done your homework. Also, let’s be honest, a solid, comprehensive literature review isn’t just informative—it shows that you really belong in the conversation.

How should I prepare the literature review before writing it?

Before you even start writing your literature review, you need to do some preparation. First, choose a topic that really grabs your attention—one that you won’t mind spending hours on. Once you’ve identified a topic, do some research: read widely, see what’s out there, and start to get an idea of where the big debates and interesting questions lie.

Next, try to compile an annotated bibliography. Basically, as you read the sources, make short notes about what each piece says, what the arguments are, and how they might relate to the topic you want to present in your review, in addition to the citations. Don’t be afraid to write reminders or highlight quotes that come to mind.

Most importantly, follow the main ideas, especially anything that supports your point of view or argument. This preparation will help you stay organized (and, frankly, save you sanity later when you’re knee-deep in sources). Once you’ve completed these steps, you’ll be ready to craft a comprehensive review that focuses precisely on what’s important.

How does an academic research paper differ from a literature review?

Academic research papers and literature reviews may seem quite similar at first glance, but they actually play very different roles when it comes to research work. Take literature reviews, for example: their main task is to help readers find out what already exists on a given topic. They draw from books, articles, and almost any reliable published research they can find. In addition, they point out gaps in knowledge or areas where scientists disagree. Imagine them setting the scene and saying, “Here’s what we know so far, and here’s the puzzles we haven’t solved yet.”

Now, academic research is taking it a step further. Rather than simply reporting on what others have done, these papers aim to offer something entirely new to the conversation. They usually delve into a specific research question and include factual data or conclusions drawn by the authors themselves. Of course, they will refer to previous work (usually in the introduction or in their enlightened review sections), but the real heart of the article lies in its original contributions. In other words, literature reviews summarize the current state of the art, while research papers push those boundaries outward, providing new insights or discoveries.

What are some techniques for composing a review of the literature?

If you’re looking at the task of writing a literature review for a research paper, you’re certainly not alone—it’s essentially an academic rite of passage. But how do you actually do it? Well, there are a few classic ways people do it, and while you don’t have to pick just one, knowing the basics helps a lot.

First: a chronological overview. As the name suggests, it’s time. You arrange your sources by when they were published, guiding the reader through how ideas have changed, grown, or (as often) changed completely over the years. This is great if you want to show how thinking has changed on a topic.

Or maybe focus on topics instead. This is where the thematic review comes in. Rather than examining subjects by date, this style groups studies around recurring themes or ideas. So if five different researchers were looking at “student motivation” from wildly different angles, you’d bring them together and explore what they have in common.

Then there is a methodological overview – a kind of behind-the-scenes look. The focus here is on how the various studies were actually conducted. Did they use surveys? An interview? Very complex statistical models? By sorting through the literature in this way, it is possible to highlight which research methods are reliable (and which perhaps deserve a skeptical eyebrow raise).

Don’t forget the theoretical reviews. This approach breaks down the literature by theory, so you dig into what big ideas or frameworks people have used to interpret a topic and analyze what those theories actually contribute.

Honestly, most good literature reviews aren’t just one thing; they are somewhat mixed depending on your research question and what literature you find. Sometimes you can even use methods like integrative or systematic review if your project calls for it.

In short, there are several ways to tackle a lit preview, but whichever route you choose (or combine), the key is to keep your goal and audience in mind. Well, don’t be afraid to get creative with things – there’s plenty of room for your own spin!

What structure does a literature review follow?

When preparing a literature review, the structure will often depend on the specific requirements of your journal, professor, or field. Still, most good literature reviews follow a familiar rhythm. Here’s how it usually goes:

**Introduction/Overview:**

Start by giving your readers a quick overview of the topic. What is this? Then be clear about what you’re trying to achieve – are you trying to outline current thinking, highlight an argument, or perhaps spot gaps in knowledge? Setting boundaries (such as time frames or subtopics you won’t touch) also helps here. And don’t forget to drop your main research question or argument; this is your anchor.

**Body:**

This is where things get interesting. Many people organize this section by topic, big ideas, or chronologically if that works for your topic. Dive in and critically analyze each set of sources – what did they find? Were their methods solid, are there any red flags? Sometimes research is groundbreaking but has glaring blind spots or odd trends; summon those Also look for patterns in your research. Several studies may agree on one point but completely contradict another. Bookmark it! Your job here is not just to summarize, but to synthesize—to connect the dots.

**Conclusion:**

Wrap things up by summarizing the main points you uncovered. Was there an obvious hole in the study? Say yes! Back to the original question, did the literature help answer it, or did it leave more questions than answers? Finally, suggest where future researchers might take action now that you’ve done the heavy lifting.

The goal is to tell a story about what is already known about your topic while gently nudging readers toward what remains to be discovered.

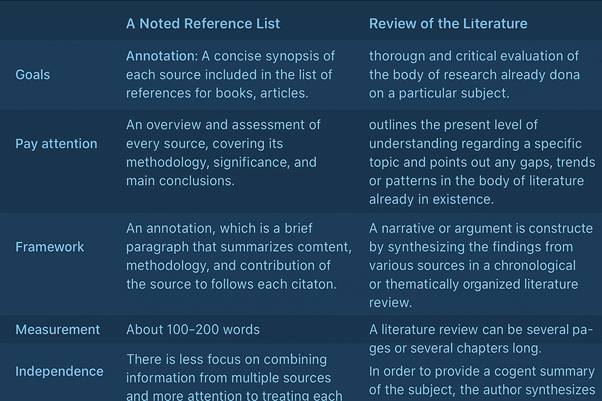

What distinguishes a literature review from an annotated bibliography?

When you browse academic sources, you’ll likely be doing one of two things: conducting a literature review or creating an annotated bibliography. Both jobs mean you have to actually look at the research, but how do you approach it? This is where things fell apart.

A literature review is essentially a story about an entire field: it brings together what’s out there, makes connections between studies, draws attention to debates, and shows how ideas have evolved over time. It’s not just about “this source said X and that source said Y.” Instead, you zoom out to see the big picture, debating how all those parts fit (or don’t) fit together.

An annotated bibliography, on the other hand, is more like a list of ingredients. Here’s Source One, here’s what it argues, here’s why it might be useful… and repeat it for every article or book you read. Each entry is self-contained, with a brief summary and perhaps a few lines about its strengths or relevance to your project.

So, in summary: a literature review brings together and synthesizes sources to tell a coherent academic story, while an annotated bibliography provides snapshots of individual works without necessarily linking them together. Both are useful, they just serve different purposes depending on what you need for your research.